Breaking the Hypnotic Spell of the Covid Death Chant

Breaking the Hypnotic Spell of the Covid Death Chant

January is reputedly the most depressing month of the year. It was made all the more depressing this year by the ever-tightening noose of Covid restrictions that preceded it. But the mood wasn’t grim enough for the mainstream media fear-pedallers, who piled on the depression with a daily Covid death count. January was simply another month that proved there is no limit to the government’s and its public broadcaster’s efforts to ramp up the Covid terror campaign.

The daily Covid death count is like a religious chant. You are not supposed to question it. You are supposed to be hypnotised by it. In a recent BBC Covid Television News bulletin, Clive Myrie repeatedly punctuated sentences with the chant: “We’re all scared” and “Dying and dying and dying”. If, however, you pause to question the foundations that give the chant its meaning, it might lose its mesmeric quality.

The pressure on hospitals, deaths within 28 days of a positive Covid test, excess mortality, the frenzied race to mass vaccinate the population and the endless refrain that lockdowns save lives – these are all part of an information fog concealing the reality that we are needlessly destroying lives. How does one reconcile the January horror stories with the lockdown sceptics’ belief that we ought to have decided to learn to live with the virus (protecting those most vulnerable) rather than devastate the whole of society, all the while drenching the general population in fear?

Hospital pressure – just how ill is the NHS?

Using the NHS Hospital Statistics website, a senior NHS doctor who contributes weekly updates to Lockdown Sceptics provided some perspective in a January 15th update, which I summarise below:

For the week prior, admissions from the community in London, East England and the South East have been falling. For these regions, admissions had peaked and were already on the downward slope and had peaked by the time the current lockdown began on 6 January. The ZOE app, far more reliable than any predictive tools the government has been using, showed a downtrend in symptomatic people from about December 31st. Although the effect (if any) of lockdown on hospital admissions would not be observable until at least January 16th, mainstream media reporting of a reduction in hospital admissions being a consequence of lockdown is a post hoc fallacy.

Under normal conditions, it is difficult to discharge elderly frail patients in winter, but Covid has delayed discharges back into care homes even further owing to reluctance by insurers to cover them for Covid outbreaks, demonstrating a perverse paradox of insurance – you insure for unexpected and infrequently occurring losses, but the more unexpected and infrequent the loss, the less likely it is to be covered by insurance. So despite admissions falling, the total number of inpatients rose because of failure to discharge.

A few days prior to the 15 January update, the BBC made a claim that there were “many more younger patients” affected by Covid in the winter than in the spring. The data just doesn’t support this. 37% of the Covid patients admitted from March 20th to April 30th were aged between 18 and 64. The corresponding percentage for the period November 27th to Jan 6th is 39%. Hardly “many more”. Age statistics on death don’t support this claim either. The total percentage of deaths in the under 59 year old age grouping during the initial outbreak in spring was 6.64%. The corresponding percentage in the period November to January 1st is 5.26%.

The above observations do not apply to the Midlands and the Northwest, which saw a rising trend in admissions and ICU occupancy, but which also suffer from less capacity than areas like London.

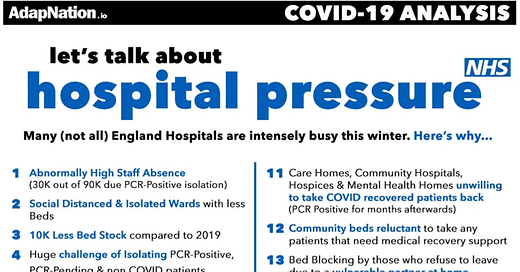

The pictorial below, taken from Lockdown Sceptics’ January 15th update and supplied by AdapNation from information provided by an NHS hospital logistics employer at a busy England hospital, shows that the picture is complex and that the catastrophising mindset that drives lockdowns became a self-fulfilling prophecy through its destructive impact.

Here is the overall England hospital picture at January 22nd and February 4th:

In seeking to justify lockdowns, the government has gone to great lengths to make Covid look like the only serious threat to public health. Bolstering this Covid tunnel vision is the claim that Covid now dominates the winter respiratory biological ecosystem, pushing flu and other illnesses into the background. Is this reality or the result of misdiagnosis due to myopia?

On January 18th, The Telegraph attempted to put the “second wave” into perspective with an article titled “Why the second Covid wave is nothing like the first”. Ofcom’s restrictions prevent the media from contradicting government propaganda messages about its measures, so the article unsurprisingly engages in a form of double-speak by making the argument for its title while also agreeing unequivocally with the ramping up of government restrictions. Arguing for the miraculous disappearance of flu deaths, it quotes Professor David Spiegelhalter, who acknowledges that “non-Covid deaths are running very low” and attributes this in part to the government’s measures against Covid:

"First of all there's almost no flu circulating, which is very big and due to the measures that have been taken [against Covid], and also that very sadly, a number of elderly vulnerable people lost their lives that are there in the spring." [The qualification in [] is The Telegraph’s, not mine.]

Are we really being asked to believe that Covid measures have been stunningly effective in mitigating flu illness but completely hopeless against Covid? No plausible arguments have been tabled to explain why measures specifically concocted to address Covid (and which have been religiously enforced because of their claimed efficacy) would accidently wipe out one respiratory virus (flu) and yet fail to eliminate its intended target. And if Covid measures don’t work against Covid, why persist with failure?

A plausible counter-argument to the mainstream media narrative is that if the only thing you’re looking for is Covid, the only thing you’ll find is Covid. The conditions for large-scale misdiagnosis are ripe with a health system fixated on Covid and using an already unreliable test in a manner for which it was not intended (general population screening as well as screening of all patients who enter hospital regardless of their symptoms). If there are no real grounds for believing and proving that the diseases which have killed in a consistent way in the past have now suddenly retreated, then it’s reasonable to posit that, other respiratory illnesses, once patients are admitted to hospital, are being sucked into the Covid statistical vortex.

Supporting this, Clare Craig, Jonathan Engler and Joel Smalley cite a study during the 2016–17 influenza season in Spain which showed that testing of recently deceased elderly patients identified a respiratory virus in 47% of them and 7% of them had a positive coronavirus test. However, only 7% of these patients had been diagnosed as having a respiratory infection before death. They go on to state three possible interpretations of the study’s finding: respiratory viruses precipitate other problems (e.g. myocardial infarctions) that then lead to death; very ill and dying patients are highly susceptible to respiratory infection, or; respiratory viruses are innocent bystanders present at death (i.e. not contributing to the underlying cause of death). A mix of all three could be at play.

The kernel of the argument is that the significance of finding a respiratory virus in the dying is uncertain and, had we been diagnosing in the ‘normal’ way and not conducting mass testing for Covid in hospitals and elsewhere, it is unlikely that Covid would be appearing on the death certificates of so many elderly frail patients.

Referring to the same study, John Ioannides, writing in March 2020, observed that:

A plausible counter-argument to the mainstream media narrative is that if the only thing you’re looking for is Covid, the only thing you’ll find is Covid. The conditions for large-scale misdiagnosis are ripe with a health system fixated on Covid and using an already unreliable test in a manner for which it was not intended (general population screening as well as screening of all patients who enter hospital regardless of their symptoms). If there are no real grounds for believing and proving that the diseases which have killed in a consistent way in the past have now suddenly retreated, then it’s reasonable to posit that, other respiratory illnesses, once patients are admitted to hospital, are being sucked into the Covid statistical vortex.

Supporting this, Clare Craig, Jonathan Engler and Joel Smalley cite a study during the 2016–17 influenza season in Spain which showed that testing of recently deceased elderly patients identified a respiratory virus in 47% of them and 7% of them had a positive coronavirus test. However, only 7% of these patients had been diagnosed as having a respiratory infection before death. They go on to state three possible interpretations of the study’s finding: respiratory viruses precipitate other problems (e.g. myocardial infarctions) that then lead to death; very ill and dying patients are highly susceptible to respiratory infection, or; respiratory viruses are innocent bystanders present at death (i.e. not contributing to the underlying cause of death). A mix of all three could be at play.

The kernel of the argument is that the significance of finding a respiratory virus in the dying is uncertain and, had we been diagnosing in the ‘normal’ way and not conducting mass testing for Covid in hospitals and elsewhere, it is unlikely that Covid would be appearing on the death certificates of so many elderly frail patients.

Referring to the same study, John Ioannides, writing in March 2020, observed that:

“In an autopsy series that tested for respiratory viruses in specimens from 57 elderly persons who died during the 2016 to 2017 influenza season, influenza viruses were detected in 18% of the specimens, while any kind of respiratory virus was found in 47%. In some people who die from viral respiratory pathogens, more than one virus is found upon autopsy and bacteria are often superimposed. A positive test for coronavirus does not mean necessarily that this virus is always primarily responsible for a patient’s demise.” [bold emphasis added.]

Subsequent to the April peak of pandemic deaths, and coinciding with the rise in mass testing, the rise in Covid labelled deaths has been mirrored by a fall in non-Covid labelled deaths. There is strong evidence, based on the expert opinion above, that this is due to misdiagnosis. So what should we make of the relatively unsupported claim that Covid measures have been successful at halting all respiratory illnesses except Covid? I’d say that taking the claim to its logical conclusion, why don’t we simply fashion some influenza measures to eradicate Covid?

Returning to the central issue of pressure on hospitals, a reasonable analysis of the position we now find ourselves in is provided by Clare Craig, Jonathan Engler and Joel Smalley. In a nutshell, a novel virus will, as all respiratory viruses have done since the beginning of time, progress from the epidemic stage in the naïve population to endemic. Being a respiratory virus, it will be seasonal and cause the biggest challenge in winter. Viruses do not disappear and nor do lockdowns have any effect on transmission in the community.

Craig, Engler and Smalley go on to remind us that a bad winter is guaranteed to put the NHS in crisis mode because the NHS has been managed into this position over the last 20 years. Against the backdrop of a growing and ageing population, the NHS has experienced a 31% reduction in beds from 240,000 in 2000 to 165,000 in 2019. The figure fell by a further 10,000 in 2020 owing to social distancing between patients in hospital. The NHS now has less than 3 beds per 1,000 inhabitants compared with Germany’s 8 per 1,000 inhabitants. Nevertheless, the capacity has not been exceeded even in regions where 30% of patients have a Covid label. Their conclusion is:

“The NHS is facing a winter crisis which has more to do with bed management and broader policy decisions than Covid itself, although the latter will be contributing as well, because it is winter and we must now regard Covid as an endemic disease (like flu)…We may find that the mix of the predominant winter respiratory viruses has changed to have a different character and whether this is permanent remains to be seen. However, the overall impact on healthcare and on the number of lives lost is not, and will not be, that different.” [Bold emphasis added.]

Using Covid to justify the colossal self-harming act of lockdown is a smoke-and-mirrors masking of a chronically ill NHS that has been in steady decline for two decades. Having successfully terrorised the public into submission, the government now has an electorate that favours decapitation as the answer to a headache. The precedent for winter lockdowns in perpetuity has been set – be prepared for the lockdown guillotine to be wielded whenever there is half a chance that the government could be ‘overwhelmed’ with front page tabloid pictures of sick patients clogging up NHS corridors.

Excess mortality

Up until December, a big problem for lockdown proponents was the absence of excess mortality or levels of excess mortality that in no way put 2020 into the grim reaper league tables. Attempting to have their cake and eat it, lockdown proponents credit pre-December low excess mortality with lockdowns but cite the emergence of successive weeks of excess death in December and January as proof that more lockdowns were necessary, despite the fact that we locked down for the whole of November. Faced with the real-life proof that lockdowns don’t work, lockdown stalwarts resort to complaining that it wasn’t done soon enough or that the miscreant general public wasn't complying sufficiently with the rules (although sufficiently to eradicate all other respiratory diseases, don’t forget).

So let’s talk about excess death in the UK. I will use headline figures for England and Wales only as it was relatively easy to find a reference for non-Covid excess death figures for this region. England and Wales together account for 89% of the UK population so this analysis should serve as a reasonable proxy for the UK.

A word of caution about the analysis: if you’re looking for something with nine graphs, each of which has five almost indistinguishable lines and a double y-axis, you’re going to be disappointed. The average person, including me, abhors those things. I’ll try to distil it to its essence so that everyone with basic maths can get it. I will go through four logical steps (I’ve inserted the main numbers into the steps below so when you encounter them later you’ll recognise them):

Establish the total excess death figure (84,000).

Subtract the estimate of excess deaths at home from non-Covid causes – 36,000. It is valid to speculate that these deaths may have been a direct result of lockdown since this level of excess death at home is something new.

Look at the remaining number (48,000) and judge how scary it is – put it into perspective by looking at the total number of people who die on average every year (530,000).

Examine the reasons why it’s very difficult to label that number as being solely down to Covid.

Step 1. All figures are rounded to the nearest thousand. The total excess deaths figure for England from the start of the pandemic (March 21st, 2020) up to January 15th, 2021 is 80,000. Adding the estimate of 4,000 for excess deaths for Wales for the same period gives a total for England and Wales of 84,000. Total Covid registered deaths in England and Wales for the same period are 95,000 (89,000 and 6,000 respectively). Do not read too much into the 11,000 surplus of Covid deaths over total excess deaths since excess deaths and Covid deaths are not the same thing, although there may be an overlap.

Step 2 and 3. Non-Covid deaths occurring in the home from the start of the pandemic up to January 1st, 2021 are estimated to be around 36,000. That whittles the maximum number of excess deaths that could be attributable to Covid down to 48,000 (84,000 – 36,000). Some perspective – roughly 530,000 people die in England and Wales every year.

Step 4. Having arrived at a net excess deaths figure of 48,000 that may or may not be solely attributable to Covid, we can now ask questions about how reliable that remaining number is. One of the problems I have with Public Health England’scommentary on excess deaths is that it makes two misleading assumptions which are interdependent – it assumes all Covid deaths are excess deaths and that, where excess death is actually less than the total Covid deaths, it assumes this is due to the compensating effect of fewer deaths from other causes. As I will argue, an element of miscounting of Covid deaths, the age-dependency of Covid death and misdiagnosis, to name some factors, all punch holes in these assumptions.

One reason why all Covid deaths do not qualify as excess deaths is that many of those deaths, owing to Covid risk being highly age and comorbidity dependent, would have occurred anyway. Another reason relates to the known unreliability of Covid death certification, which is dealt with later on. With regard to the supposed compensating effect of fewer deaths from other causes, this assumes misdiagnosis could not be a contributing factor to this negative swing in excess death. This, as I have already argued, is highly unlikely.

So can we safely say that 48,000 excess deaths in England and Wales are attributable to Covid? No. The figure is likely to be lower, and here’s why. Every hospital admission, no matter what the reason, is accompanied by a Covid test, the unreliability of which is acknowledged by all except the government. Even the criminally negligent WHO has finally acknowledged the problems with PCR testing that had already led many respectable medical experts to conclude that the hysterical escalation of the pandemic was started by mass testing and could have just as rapidly been ended by a cessation of such testing. A longer hospital stay correlates with a more serious illness. It also correlates with increased frequency of unreliable PCR tests. A Covid death is defined as a death within 28 days of having tested positive for Covid. Malcolm Kendrick, a frontline doctor, explains the implications:

“With COVID19, this is a massive problem. In the UK, and several other countries if you have had a COVID19 positive test (which may, or may not, be accurate) and you die within twenty-eight days of that positive test, you will be recorded as a COVID19 death. I do not know much for sure about COVID19, but I do know that is just complete nonsense.

There are so many cases where – even if the COVID19 test was accurate – COVID19 would have had nothing whatsoever to do with the death. Another thing known, or at least we probably know, is that the vast majority of people who die had many other things wrong with them.

In the US, the Centre of Disease Control (CDC) found that ninety-four per cent of people who died of COVID19 ‘related deaths’ had other significant diseases (co-morbidities). This ninety-four per-cent figure would only be the co-morbidities that were known about – who knows what lurked beneath? Especially as people stopped doing post-mortems (i.e., autopsies in the US).

So yes, they had COVID19 (or at least they had a positive test – which may not be the same thing), but they were often very old, and already severely ill. Using an extreme example, someone with terminal cancer who is a week from death, catches COVID19 in hospital, and dies. What killed them? The statistics say COVID19. I say, bollocks.”

Aside from the very shaky basis of Covid death certification, there is also a strong tie-in here to points made by Craig, Engler and Smalley and Ioannides when they referenced the Spanish study that looked at diagnosis of the cause of death in deceased elderly patients and the questionable significance of the presence of respiratory viruses at the time of death.

Here’s something that won’t get reported widely in the mainstream media: a recent study carried out in Stockholm found that only 17% of those who supposedly died of Covid in care homes actually had Covid as the primary cause of death. Put another way, the Covid cause of death figures in care homes were inflated by 588%. Put yet another way, reported Covid deaths in care homes were nearly 6 times greater than the actual figure.

So can we be reasonably certain that excess deaths attributable to Covid in England and Wales are lower than 48,000? Yes. How much lower? Who knows.

One last reason to be highly suspicious of Covid making such a significant contribution to excess mortality is that it disproportionately affects people at or very near the end of their lives. The vast majority of those who die of or with Covid would statistically have died anyway around the same time Covid took them. Dr David Cook, a senior scientist with decades of experience in pharmaceutical research, articulates this basic truth:

“COVID-19 hits older and more vulnerable individuals harder than younger, fitter individuals. As a result, the majority of deaths and serious illness are in the older, sicker population. This doesn’t mean that some younger or otherwise apparently healthy people can’t die or have significant illness, it is just a lot less common in this group.”

The average age of death from or with Covid in England and Wales is 83 (click on the excel link). The average life expectancy is 81.25. The position up to January 15th, 2021 is that 75% of deaths ‘involving Covid’ have occurred among people aged 75 years and over. It’s therefore no exaggeration to characterise Covid as being, statistically, more of an end-of-life illness.

The objective in all of this is not to prove that hospitals aren’t under pressure, that Covid is ‘fake’, or that there is a ‘tolerable’ level of excess mortality. Rather, by examining hospital pressure and the Covid death count more rationally and questioning their foundations, we can judge whether the levels of fear and hysteria generated by the media and the government are reasonable. If you think the answer to that is ‘no’, that opens up a conversation about how we as a society allowed things to get to the point where the national broadcaster thinks it is appropriate for its news reporters to dramatise death in this irresponsible way instead of calmly reporting carefully analysed facts.

Whether the excess mortality is 84,000, 48,000 or less is also to some extent irrelevant. The unavoidable question that is left, regardless, is whether it would have been worse in the absence of lockdowns. Even if that answer was yes, you would have to carefully weigh the damage done by lockdowns against the benefits. However, the case for lockdowns is now widely acknowledged to be morally, intellectually and economically bankrupt but with the government releasing a report at the end of January claiming that the number of Covid deaths would have been significantly greater in the absence of lockdowns, it is important to keep restating the case against them. I intend to do exactly that in my next blog.